It was the period of the women’s suffrage movement at the turn of the century…

The fight for equality in the field of Fine Art was just as difficult as their fight for the vote. For the most part, American women painters who worked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries got a raw deal from their male counterparts. Their unenviable lot in life owed mostly to male chauvinism inside and outside of the art community. It was bad enough for a talented, beginning male student but nearly impossible for a young woman to become a successful professional artist. The odds were not in their favor. Usually their efforts, regardless of quality, were sidestepped by the art hierarchy because they were looked upon not as serious art students but as pretty young things seeking husbands.

Many talents did find matrimony in the art field and a few of these married women, such as Lilly Martin Spencer, Lilla Cabot Perry, Harriet Randall Lumis, Gretchen Rogers, Gertrude Fiske and others, did achieve admirable reputations. But in spite of their skills and creativity, women’s careers were fraught with socio-cultural struggles. The inequality was obvious but even certain women themselves cast doubts about the veracity of women artists. For example, in the late 19th century a woman wrote:

“to the vast majority of women it is impossible to practice art after marriage. Either it will be poor art, or an unkempt family. It is true, we cannot serve two masters.”

Lillian Westcott Hale

"Blue Taffeta"

Oil on Canvas: 48 x 30 Inches

But notwithstanding the implicit reference to a bible passage, the statement didn’t ring true to Louise Cox who in 1895, wrote a reply saying, “women writers marry [and] women musicians marry; why should artists be in a class by themselves?” Yes indeed, why should they, was the attitude of Lilian Westcott, a woman painter who believed that women had a right to compete with men in art circles. Miss Westcott continued studying under two great American teachers: Edmund Tarbell and William Merritt Chase, both of whom we might refer to as impressionists. Accordingly, the exceedingly talented Miss Westcott practiced her skills at painting and achieved high praise. However, eventually Lilian became Mrs. Philip Hale, and her husband was also a painter of high rank in the American art community. In spite of her own struggles to become recognized as a serious art maker, Lilian Westcott Hale developed into a highly successful impressionist whose husband supported her in every way.

But not all husbands of painters were as kind. In fact, a woman from Indiana known to art historians as Fra (pronounced Fray) Dana also studied with Chase at the Art Students League in New York and with Joseph Henry Sharpat the Cincinnati Art Academy, Alfred Maurer and Mary Cassatt in France. Sharp was proud of Dana and was quoted as saying, “She paints like a Man.” Nonetheless, Miss Dana married a cowboy, a rancher from Wyoming who had devoted his career to cattle ranching and found little use for art, especially that which was made by his wife. She was expected to work on the ranch but an agreement with her “culture-less” husband allowed her some time to study in New York and Europe. She became an outstanding painter but she was obliged to return to her life as a rancher. A letter from her diary of 1907, in which she revealed:

“I remembered it was Velasquez’s birthday, a strange place it was to remember. This is life and the thoughts I used to think were dreams. Beauty of any kind is a thing held cheap out here in this land of hard realities and glaring sun and alkali. . . .”

In spite of Cassatt’s advice to Dana to become “ruthless” in an effort to survive, she (Dana) was unable to leave Wyoming where at the end of her life she wrote: “My annals are short and simple. I was born, I married, I painted a little, I am ready to die.”

Not every woman artist gave up as a result of marriage. Indeed, there were some who valued their God-given talent so highly that they rejected marriage and chose to make art instead of babies. One of the most famous of these unmarried professionals was Mary Cassatt, a true American impressionist from Philadelphia who spent her adult career as an expatriate in France. Standing out as a shining example of a truly successful woman artist, Cassatt was an inspiration to many young women hopefuls. Lilla Cabot Perry was another successful painter whose marriage was helpful to her career. She traveled with her husband to Claude Monet’s home in Giverny, France where she participated in the American expatriates’ inauguration of American impressionism. While living next door to Monet, Perry was one of the few to receive the French master’s technical advice. Meanwhile Mr. Perry, a professor at Harvard, was enjoying what he called being an “exile” from Boston, and he sent back reviews of art exhibitions to the Boston Evening Transcript. Besides Monet, the Perrys befriended Pissarro and attempted to promote his works. Moreover, they helped to introduce French impressionism to Boston’s art scene by bringing back freshly painted canvases by both French and American impressionists.

Other American women artists changed their minds in midstream. Such was the situation for Elizabeth Russell, the subject of a short story by Eleanor Hoyt, “Women Are Made Like That” (Harper’s, November 1901). Miss Russell, an expatriate in Paris, became engaged but before marriage submitted a portrait of her fiancé to the Salon. “My picture was not only accepted but displayed prominently and received critical praise.” Inspired by her new success Miss Russell canceled her wedding plans, explaining, “I would hurt you more if I married you. Art was always first.”

The anxiety that existed for women as they chose between marriage and an art career was well known at the turn of the century. Not many women were able to find a balance between two careers – usually marriage and children came first. But if the American art world suffered from the loss of female talent, somehow it didn’t seem to matter because there was an ample supply of new young hopefuls to fill the lack. In an article on the Boston Museum School’s 25th anniversary, the Boston Herald reported that many graduates of the School are among the country’s leading artists and “many of the most talented of the graduates have been women.”

A perusal of paintings from this period will arguably reveal that a majority of pictures from the hands of women painters are figurative. Moreover, many of these focus on family life, including the activities of children and the mother and child motif made famous by Cassatt. Painters who achieved credentials in this genre were Marie Danforth Page, Gretchen Rogers, Sarah Wyman Whitman and many others. These subjects were considered “typical” of women painters at that time.

But certainly not all were figurative artists, for some such as Harriet Randall Lumis were outstanding landscapists. In fact, Lumis' work was so highly regarded, she was able to make a living from her art. She was married but unencumbered by children as she painted marvelousscenes in and around Springfield, Massachusetts and elsewhere. Harriet Lumis’ career was proof that a woman could make a living from her art and help support her husband.

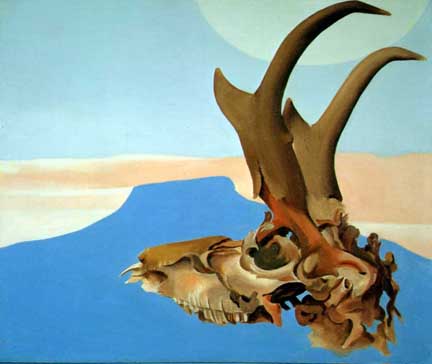

Georgia O'Keefe

Antelope Head

With the triumph of modernism and abstract art, the traditional exclusion of women from academic drawing instruction was no longer an issue. America would produce outstanding women artists who were significant within an international milieu, such as Georgia O’Keeffe. She was one of the early American modernists promoted by her husband Alfred Stieglitz in his avant-garde Gallery 291 in New York City. In 1916 the unknown painter born in Wisconsin reportedly sent her drawings to a friend in New York with instructions to show them to no one. Georgia’s friend took the drawings to Stieglitz against her wishes. In another version of the story, O’Keeffe expressed how she would value Stieglitz’s approval. Stieglitz was more than pleased and her career was set in motion. In his photography and in her paintings, both artists shared a certain way of seeing. Later, in 1924, O’Keeffe and Stieglitz were married: he was sixty and she thirty-seven.

As the 20th century’s art community began reflecting the liberation of women in America, its women painters were frequently praised as innovators. Not only did the fetters of male chauvinist culture fall away, some women exceeded their male counterparts a good deal. But I think it’s important to recall the many injustices experienced by women artists of a century earlier as a constant reminder that all Americans be given the full right to compete at every level, especially in art, a product of either gender.